The Black Arts Movement And Beyond

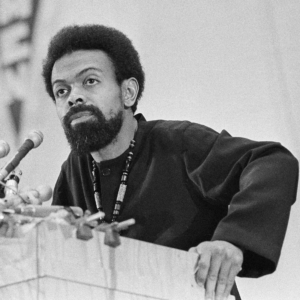

Amiri Baraka

“We want poems that kill”

–Leroy Jones (Amiri Baraka), “Black Art,” 1965

Seriously. Amiri Baraka created the Black Arts Repertory School–BARTS–Theatre in Harlem in 1965 following the assassination of Malcolm X, and for him, art was to be a cultural weapon. The literary poems, plays, and essays by African American writers Stephen Henderson, Larry Neal, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks and others between the mid-1960’s through the mid-1970’s emphasized radical political action as the goal of art. They were the founders of the Black Arts Movement, which was considered the artistic “sister” of the Black Power Movement.

While Toni Morrison was not a part of this group, her works, and that of many other African American writers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, have some aspect of the movement as a touchstone. In this blog, we will consider the following questions:

1. What was the import of the Black Arts Movement for African American literature?

2. What were some of the philosophical discourses about black aesthetics following the end of the movement?

3. In what ways, if any, has the Black Arts Movement impacted Toni Morrison’s work, especially her Black Musical Aesthetic (see the Black Musical Aesthetic blog)?

4. What other sources, besides the Black Arts Movement, are key influences on Morrison’s art form?

Radical Black Activism

First, the Black Arts Movement emphasized radical black activism, art-in-the-street and in-your-face, as it were, and according to blackpast.org (2019), it set the aesthetic foundations for rap and other spoken-word art forms in contemporary African American culture. Poetry and plays were the primary genres of production in this 1960’s-70’s period, though, including the play, The Flying Dutchman (Jones/Baraka), and the poem, “And still I Rise” (Maya Angelou).

Maya Angelou

There were magazines and journals dedicated to the movement—The Liberator, Freedom-ways, The Journal of Black Poetry, Black Scholar, and Negro Digest/Black World—as well as widely recognized literary anthologies such as Black Fire and Understanding the New Black Poetry. And throughout these numerous works and performances, there was a “functional level”: the “dialogic responses to the racism of the dominant culture” (Ingrid Monson).

According to historians, the movement declined due to both external pressures (the IRS and other institutions of the U.S. government shook up Black Power sites, including those of the Panthers, as well as art venues) and internal differences, as some members trended towards Marxism and Afro-Centrism. Marxist critiques of literature became dominant, and social realism was to be the mode of African American literature; anything else was to be critiqued. This was the case with Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, was criticized by Richard Wright and others for its imaginative emphasis on the protagonist’s mind as having overcome his social status. But the tide began to turn, so to speak.

Do Your Art the Want You Want

Secondly, then, there were several turnings away from the Black Arts Movement’s tenants, and one most influential ones came along with the publication of Ishmael Reed’s novel, Mumbo Jumbo, in 1972. A novel of political humor and multi-cultural history that resisted the social-realist model, which Reed critiqued as that “heavy Russian Dostoevskian din of intense pain,” Mumbo Jumbo can be appreciated (and enjoyed!) as one of the first multi-cultural novels. (The literary organization and journal dedicated to such work was founded not long after: MELUS, the Society for the Study of Multi-cultural Literature of the United States).

Another key development in evolution of the concept of black arts came with the development of African American literary theory in the 1980’s and beyond. Two influential works by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. —Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the ‘Racial’ Self (1987) and The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Creation (1988)—established the sophisticated aesthetics and the cultural roots of African American literary forms. No longer could critics dismiss black writing as sociology.

“’Blackness’ is not a material object, an absolute, or an event, but a trope; it does not have an ‘essence’ as such but is defined by a network of relations that form a particular aesthetic unity. Even the slave narratives offer the text as a world, as a system of signs.”–Henry Louis Gates, Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the Racial Self.

The Blossoming of African American Women Writers

Third, Toni Morrison’s works were initially viewed as some of the major contributions to the blossoming of African American women writers from the 1970’s through the 1980’s, along with Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Gayle Jones, Gloria Naylor, N Tozake Shange, and so many more.

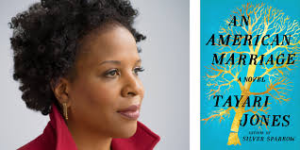

Tayari Jones

Black women writers were anthologized widely during this period, and their influence on more contemporary African American writers–Nikki Finney, Natasha Trewethey, Tayari Jones, Jessamyn Ward, to name but a few–goes without saying.

Currently, Toni Morrison is considered one of the world’s greatest writers of the century, with accolades and critical commentaries too numerous to elaborate. The Black Arts movement of the 1960’s and 70’s seems far away now in many respects, but is it? Some features of its breakthrough-status are still embedded in literatures of today around the world, including Morrison’s. I quote Ishmael Reed in a 1995 interview (recall from above that, decades earlier, Reed railed against its hegemony:

I think what Black Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would be no multiculturalism movement without Black Arts. Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the example that you don’t have to assimilate. You could do your own thing, get into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture. I think the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Black Arts struck a blow for that.

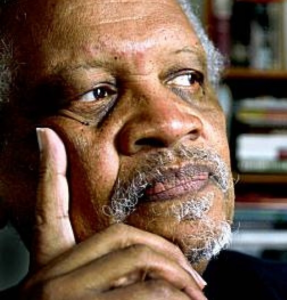

Ishmael Reed

Cultural soverignty is very central to Toni Morrison; statements from her interviews emphasize the “indisputably black” form and content of her work. Moreover, another relevant goal of the Black Arts movement that has seen sophisticated development in Morrison is to create Black literature as a group effort of collaboration: it emphasizes authors and their audiences in a call-response format. And there is the “functional” level of a black aesthetic that forms a counter-response to racism.

Resisting Structures of Knowledge

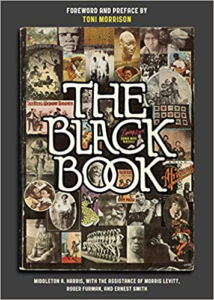

Fourth, The Black Book, which Morrison co-edited (1974), is another foundational piece to the development of Toni Morrison’s works, especially the Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise trilogy. Morrison’s essay, “Behind the Making of The Black Book,” provides an important context for the selection and arrangement of the book’s contents. Born in 1931, Morrison was in her thirties by the time the declarations of “Black Power” overtook the non-violent civil rights discourses of the early and middle 1960’s: “I have never seen Black people so preoccupied with the man as I do now. It’s as if all those Black children had their brains shot out just so we could wear a kente cloth bikini in ‘our own’ magazine (that looked just like ‘his’ magazine)” (Morrison “Behind” 87). And thus she describes how she began working on “a genuine Black history book” which, significantly, “has no order” but “does have coherence and sinew”: “it can be browsed through from the back forwards or from the middle out, either way” (89, emphasis added).

The Black Book

Resisting the structures of knowledge which “order” entails, the Black Book’s multiple-directionality for “browsing” anticipates the recursive patterns in Morrison’s three-novel project. Furthermore, alongside major African American’s achievements–such as the invention of the cotton gin, medicines, and military contributions–there are reproductions of “blackface” cartoons and Aunt Jemina. Every type of black life in the U.S. was to be represented (The volume also contains a 19th century newpaper article about Margaret Garner, the inspiration for the novel Beloved) in this “hodge-podge” of “Black Presence” (Morrison, “Behind”).

Responses Invitation: Reflect, Write, Post:

What are your thoughts about the Black Arts Movement if you are familiar with some of the works and history?

Or, what do you think about the issue of social-realism? Is it necessary for black literature to have the functional impact that is desirable; namely to counter racism?

Next up: two more Aesthetics blogs: Morrison’s Descriptive Vivacity will lead the way to some specific features of Morrisonian style.