Making Time

“Black people . . . have been simultaneously deprived of time and fixed in it by the color of their skin” —James Baldwin

Ksenia Makagonova /Unsplash

In Black Time: Fiction of Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States (1981), Bonnie Barthold states that in much African American literature, there is a practice of “making time” in the face of being excluded from it: “From one point of view, the history of black people during the past millennium has been the history of a people’s rebellion against the uncertainties of time, a balancing act of circumstance and heritage” (18).

What can “making time” mean? Creating agency, for one. To not be “fixed” in a static stereotype; to refuse to give in to despair or hopelessness; to “make a way out of noway” (African American Vernacular expression) when “your time” was not yours because it belonged—you belonged— to someone else. And in Morrison’s Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise trilogy, time has to be made, or perhaps remade, through memory.

Twin Exigencies: Remembering and Forgetting

In this blog section are several tools to gain sharpness in focusing on the overwhelming themes of memory in Morrison’s fiction, for it is through the juxtapositions of memories that her characters’ emotional experiences unfold. And it is through the juxtaposition of timespaces in the text—through the use of narrative sequencing using flashbacks, for example—that the readers participate in the making of time in the text. This first blog in the series will deal with the following question:

Why is remembering such an emotional experience for for Morrison’s characters and how does Morrison dramatize it?

“Rememory” is Sethe’s term in Beloved for describing how a time and place from earlier history can reassert itself with tangible consequences into the world of the present for the subject who remembers. Sethe believes that it is her job to keep her youngest child, Denver, safe from Sweet Home, the plantation in Kentucky where Sethe was a slave, even though Denver had never been to Kentucky (42):

I was talking about time. It’s so hard to believe in it. Some things go. Pass on. Some things just stay. I used to think it was my rememory. You know. Some things you forget. Other things you never do. But it’s not. Places, places are still there.

Craventure Media /Unsplash

If a house burns down, it’s gone, but the place–the picture of it–stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there, in the world. What I remember is a picture floating around out there outside my head. I mean, even if I don’t think it, even if I die, the picture of what I did, or knew, or saw is still out there. Right in the place where it happened.

“Can other people see it?” asked Denver.

“Oh, yes. Oh, yes, yes, yes.” (Beloved 43-44)

Sasa and Zamani

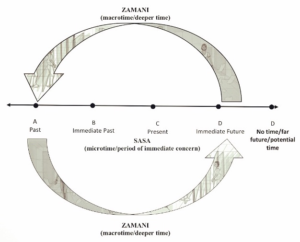

So a past event in a distant geographical location is believed by Sethe to possess the power of repetition; even someone who was never there can re-experience it. The West African framework of Sasa and Zamani—that the recently dead can “return” to visit the present– can contextualize Sethe’s belief in the palpableness of past experiences, places and people. See image below.

Black Quantum Futurism /nodecenter.org

“Rememory” is furthermore a significant neologism in an aesthetic context; it is based in the black vernacular. Sethe transforms the noun “memory” into a verbal-noun by combining it with “remember.” Writers as diverse as Zora Neale Hurston, Amiri Baraka, Geneva Smitherman, and Nathaniel Mackey have argued that African American vernacular forms are creative, and the emphasis on verbs, as in “cook-pot” and “chop axe” (Mackey, 515) “linguistically accentuates action among a people whose ability to act is curtailed by racist constraints.”1 The black vernacular “rememory” resists the dominant standardization and thus creates some freedom for Sethe to assert subjective agency: it’s how she makes time.

Responses Invitation: Reflect, Write, Post:

How can non-West Africans understand sasa and zamani in their own experiential terms? For instance, reflect, write, or post on what differences there are in your remembrances of your ancestors: the ones you knew personally vs. the ones whom you’ve not met but have heard all about, seen in photos or sketches? had to imagine?

The next blog I suggest in this Time and Memory blog cluster, Rhythms of Memory in Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise.

And please sign up to receive timely and relevant Newsletters at the bottom of the page!

1 See Mackey’s “Other: From Noun to Verb” for a discussion of Hurston’s “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” Baraka’s Blues People, and other sources on the emphasis on verbs in African American vernacular, pp.515-23.