Slave Ship Geography

“Ain’t nobody prayin’ for me. Ain’t nobody prayin.’”

—Kendrick Lamar, lyrics from “Feel” (2017 Damn album)

Late in Beloved, we readers find ourselves inside of a slave ship through the first-person narration of a young African girl. She is crammed together with hundreds of other captives headed across the Atlantic to be sold as slaves; many of whom are “trying to leave their bodies behind” (249). But: this girl? Her story survives, and her tender, young speech can blow your mind.

Late in Beloved, we readers find ourselves inside of a slave ship through the first-person narration of a young African girl. She is crammed together with hundreds of other captives headed across the Atlantic to be sold as slaves; many of whom are “trying to leave their bodies behind” (249). But: this girl? Her story survives, and her tender, young speech can blow your mind.

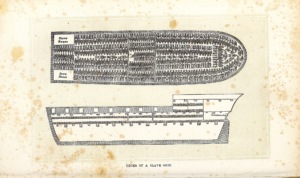

Beyond “Stowage”: the Readers’ Emotional Imaginaries

Regard the above diagram of “stowage” of the British ship Brookes under the regulated slave trade act of 1788,1 indicating how bodies are to be most efficiently organized for maximum-yield shipment to the Americas. This well-circulated image established a sort of dominant geography of the typical slave-ship, its contents an abstraction of lines and planes.

Our gaze into the slave ship interior is positioned above and alongside it: not inside. Nor does the diagram evoke living captives. By relocating the readers’ temporal and spatial orientations to a chronotope (timespace) within the slave-ship, Morrison creates an opportunity for her readers. We can rechart our emotional imagining of the Middle Passage.

Spoiler Alert: the sequences discussed here form a “big reveal” in the novel in the sense that it links the girl Beloved, who appeared out of nowhere in front of Sethe’s house, to the somewheres of abandoned girls: one on a slave-ship, one under a bridge, joined across time and space.

In this blog, I hope to open up some of questions that this challenging section of Morrison’s novel raises about time, memory, and geography:

The girl-child’s language is very stylized. Nevertheless, a more adult point of view is operating through it. How can we/do we interpret her?

Narratively speaking, why does Morrison do the complicated thing of merging the girl-child’s monologue within a triple-interchange, the call-response internal monologues/disembodied thoughts of Sethe, Denver, and Beloved?

How do we, the readers, feel about this section?

Interpreting the Girl-Child’s Language

kassoum_kone /pixabay

As a child on board a slaveship, her focalization is in a present-tense, first-person narration. Her broken syntax coalesces on the page into almost unspeakable, yet poetical, concrete details of herself and the two others who are trying to die. The first scene she narrates is actually a prior memory (though still in present tense) of when she and her mother were captured in a field; the “clouds getting in the way” of seeing her mother “take flowers away from leaves” (248) suggests picking crops under a cloud of smoke from gunfire (253). The mother is seen with a “circle” around her neck, and the child would like to “bite it” off (249). Some of these images launch a repetition-with-difference motif.

Two core emotional episodes take place on the slave-ship. First, the girl describes herself as “always crouching” and observes the man on her face has managed to die with a lingering smile and “locked” eyes. When his body is taken away, she declares: “I miss his pretty white points,” suggesting the man’s teeth (249). Readers: do we know if she was truly seeing a smile or a death grimace? And the language of him “trying” to die? Whose perspective is that?

While child-language also accounts for the desecrations by the ship’s crew, those “men without skin” (white people) who gave the Africans “their water” and “sweet rocks to suck,” the adult readers are left wondering: are these references to urine and feces of the crew?2 This is hard.

Another emotional episode occurs on the upper deck of the ship, as the child’s language then shifts to describe something happening there. People—both the living and the dead—have been brought up from below. In the middle of the deck is “a pile” of dead people to be pushed overboard. Most significantly, the woman “with my face”? And this mother-woman, alive, is not pushed: she chooses to go overboard with the pile.

Narratively Speaking . . .

Woman closing her eyes. Fauxels /Pixels

The slave-ship chronotope is embedded in a larger, also other-worldly timespace, that of the three narrations of the characters of Sethe, her daughter Denver, and her daughter/traumatized survivor Beloved, in what has been termed a “threnody” of the women calling and responding to each other’s individual stories of the mother-child relationship, the neediness and possessiveness of the love bond.

The transition, or traversal, into this other-worldly mingling of voices begins when the man called Stamp Paid knocks on the door of the house, but no one answers. And their voices, we are told, “mixed in” with the other disembodied voices surrounding the house, the ghosts of the dead. The last words of this real-time section introduce what is to come as “unspeakable thoughts, unspoken” (235). This section is offered up to us by the omniscient narrator (author).

For me, it seems as though a slave-ship child’s narration bursts through, in the language of the novel, from “the other side.” She seems to join with the girl Beloved who has been staying at 124 Bluestone Road for several months.

At any rate, because we do not encounter the staggering vision of thousands of ships filled with human trade over decades; because we are “seeing” from inside one of those ships, feeling what the girl-child felt, we can carry her geographic relevance with us in memory.

Responses Invitation: Reflect, Write, Post

Consider Toni Morrison’s statement in an interview with Marsha Darling that “the gap between Africa and Afro-America and the gap between the living and the dead and the gap between the past and the present does not exist. It’s bridged for us by our assuming responsibility for people no one’s ever assumed responsibility for.”

What does that mean to you? You might consider using that syntactical spelling that Morrison has used how can we “re-member” her?

This blog is one of several that I really liked, but had a hard time, doing; connecting the body with history in a ways that would honor Toni Morrison’s work in this area. Go on, you can do it: A Ghost with a Sword: Morrison’s Enchanted Ones. And then there’s the last blog in the geography cluster, Some Genesis Time: The Epilogues framing Morrison’s Trilogy.

And you can sign up for our Newsletter at the bottom of this or any page.

1 The image is in the public domain and is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3a34658

2 My evidence for making this inference is when the girl-narrator states that “we cannot make sweat or morning water so the men without skin bring us theirs [sic] one time they bring us sweet rocks to suck.” Just prior to the mention of the “sweet rocks,” there is the image of feces being produced by “some who eat nasty themselves” (Beloved 248), so this interpretation, as horrific as it seems, is plausible.