Morrison’s Descriptive Vivacity

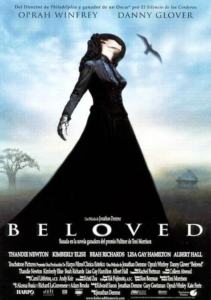

Jonathan Demme’s film image, on cover of novel

If you work very carefully, you can clean up ordinary words and repolish them, make them seem alive again. –Toni Morrison interviewed by Nellie McKay

Why a separate entry on description per se? Because there is every good reason for readers of the trilogy to respond to her descriptive artistry as such, without suborning it to other developments (thematic, dramatic) in the texts. Let’s go to one of these powerful descriptions, from Beloved:

“A FULLY DRESSED woman walked out of the water. She barely gained the dry bank of the stream before she sat down and leaned against a mulberry tree. All day and all night she sat there, her head resting on the trunk in a position abandoned enough to crack the brim in her straw hat.” –Beloved

Imagine how heavy her 19th century, full-skirted dress would have been! And, as the narrative goes on, this 17 or 18-year-old may have, well, been living in that watery place, as a ghost of Sethe’s dead daughter, returned to the world at the age she would have been had she lived. No wonder her extreme weakness. Of all the book covers for Beloved over the years, this one captures the young woman best: from Jonathan Demme’s film production of Beloved.

Such a vivid extended image like this—she came out of the water in her dress, shoes, gloves, hat!— is fundamental to narrative storytelling, and in Morrison’s hands, imagery does powerful artistic labor. This blog, and the one after it, will address the following points:

1. Images are at the root of Morrison’s creative storytelling; she says that her work moves from image-to-text. How can imagery be so vital to her readers?

Dynamic Imagery

“If you can see the person experiencing the thing, you don’t need the explanation . . . . You could use a lot of rhetoric, but you don’t need to if you simply see it.” –Toni Morrison interviewed by Claudia Tate

Ronnie Overhate /Pixabay

Toni Morrison’s descriptive style is one of the hallmarks of her body of work. From an affective-neuroscientific perspective, the more concrete details surrounding an individual’s emotional reaction, experience, or reflection, the more intensely he or she will feel them. Art critic Elaine Scarry calls this “sensory vivacity.” As readers, we have simulations of emotional experiences with concrete images from the text. For example, a character might think or say out loud something about a concrete thing or sensation—as in “These my hands?” the question Baby Suggs asks herself in Beloved—and readers are immediately struck by what all is implied or suggested by such a phrase.

So descriptive imagery is much more than delicious “icing on the narrative cake” (pardon the pun). Literary theorist Michael Riffaterre, in fact, argues that “description is primary to narrative unfolding.” (“On the Diegetic Functions of the Descriptive”). Seeing the modes of description and narration as “complimentary” and that there is “no sharp cutoff between” them, Riffaterre gives us readers of Toni Morrison a really useful perspective:

oldhousenight /pexels

Far from being essentially the lexical stuff that narrative mobilizes and with which it develops the chain of events, far from being a means to the narrative, far from being secondary to the narrative structures, description generates the narrative. . . . . the descriptive system needs only to be given a sequential structure and a temporal dimension to become narrative (Riffaterre, emphases added 282).

Toni Morrison has discussed the significance of imagery in her work in analogous ways, not only as a developmental aspect of moving her narratives along, but also as the very source of her story making. In her key essay, “The Site of Memory,” we learn that for her, writing is not only “thinking and discovery and selection . . . .” For example, as in writing Beloved:

“[I]f I’m trying to fill in the blanks that the slave narratives left . . . then the approach that’s most productive and most trustworthy for me is the recollection that moves from the image to the text. Not from the text to the image. (“Site of Memory” 113)

Marfis /Flickr

One way to consider such a key image is to see it as a “shimmer.” The shimmer denotes a dynamic, rather than static picture, with an energy suggesting action or movement.

Morrison has her own metaphors for this type of image, though, which she describes in two key essays about her writing process. When she decides in Beloved to describe the corn stalks shaking, as newlyweds Sethe and Halle lay beneath them making love, she states in her “Site of Memory” essay that she is creating a “nimbus of emotion” (119). Similarly, in the opening of another essay, “Memory, Creation, and Writing,” Morrison states that she wants the visual depictions in her fiction to evoke a “galaxy of feelings.” Not just a scene, but its “specific milieu” (385) of associative characteristics.

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post

In Beloved, Morrison has the girl Beloved turn away in disappointment and jealousy from Sethe and Paul D’s intimacy as he is climbing out of a bathtub and hugging her:

Beloved turned around and left. Denver had not arrived, or else she was siting somewhere outside. Beloved went to look, pausing to watch a cardinal hop from limb to branch. She followed the blood spot shifting in the leaves until she lost it and even then she walked on, backward, still hungry for another glimpse. (Beloved 119)

Cardinal /Flickr

How do you respond to the imagery of the cardinal and Beloved looking at it? How might it be a “nimbus” or “galaxy” of emotions?

Next up, another blogpiece on descriptive artistry in Morrison. Its title says it best: “Feathered Things” and “Long-ago Places”: Motivic Morrison.