Autobiographical Reflections on Race and Response-ability

Gordon Parks, “Department Store, Mobile. Ala.” 1956 /Adamson Gallery

For four centuries, virulent and destructive racism against African Americans has deeply inflected the moral, ethical, and cultural networks of all Americans. Black men, women, and children have developed many forms of resistance to that racism, from political communities and activisms to artistic resistances that comprise freedom.

It is through their courage and love for the human that I must try to place my own history in relation to racist practices of my homeland. I cannot not discuss it. So bear with me: my approach is through memory and personal reflection, and the piece is long.

Here it Comes . . .

How dare I, a (supposedly) caucasian, well-educated, and thus privileged female, discuss the scope of African American history and culture in which Toni Morrison works are embedded? I ask myself that question on a continual basis. This piece in no way argues my “bona fides” for discussing Toni Morrison’s work; that egoistic notion—am I “qualified” or not?—is beyond my intelligence at this point (and as I state on the Support Page, this is a not-for-profit project; please consider making a contribution to one of the organizations listed there which support African Americans).

What I can claim is that I am drawn to her work, and want to talk about it with others; and I have happily been reading, writing about, discussing, and celebrating Morrison’s fiction and non-fiction with many devoted readers and scholars through the Toni Morrison Society for the past two decades. I joined the Toni Morrison Society and went to my first TMS Conference in Lorain, Ohio—“Toni Morrison and the Meanings of Home”—in the fall of 2000.

Carolyn Denard, Board Chair and co-founder of The Toni Morrison Society

I am so grateful to many colleagues, especially Carolyn Denard, TMS Founder and Board Chair, for the welcoming opportunity to come together to consider how to teach Toni Morrison’s work and how to disseminate the importance of it—for artistic as well as political discourses—to the general public.

The first time I picked up a book by Toni Morrison, which was her first, was The Bluest Eye. I had just read Meridian by Alice Walker (1976) in which the young woman, Meridian, is physically ill but spiritually powerful. When I read The Bluest Eye (actually published 5 years before Walker’s novel), I responded with a cold, staticky feeling of dread as the girl Pecola, used and abused, spiralled down toward insanity in Lorain, Ohio (Morrison’s birthplace). I preferred the volatile warmth of Walker’s Mississippi to the cold, grey of Morrison’s Ohio.

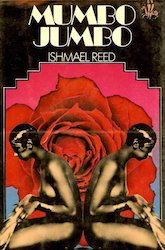

Actually, I wrote  my Doctoral dissertation on several writers, among them Ishmael Reed and Ralph Ellison,

my Doctoral dissertation on several writers, among them Ishmael Reed and Ralph Ellison,

African American writers who captured my imagination and fed my intellect in profound and lasting ways (Invisible Man and Mumbo Jumbo, respectively, remain on my favorite novels list), along with other notable writers I gathered together under the thesis of innovative identity creations in works of the American mid-twentieth century and beyond (Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Maxine Hong Kingston, Tom Robbins). Three years after finishing my PhD and settling into my first teaching position at Rutgers University, I read my second Toni Morrison novel which had just come out: Beloved. My research interests began to narrow in 1989, as I presented two successful conference presentations and published an article on Beloved based on them in 1995. I joined the Toni Morrison Society in 2000.

African American writers who captured my imagination and fed my intellect in profound and lasting ways (Invisible Man and Mumbo Jumbo, respectively, remain on my favorite novels list), along with other notable writers I gathered together under the thesis of innovative identity creations in works of the American mid-twentieth century and beyond (Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Maxine Hong Kingston, Tom Robbins). Three years after finishing my PhD and settling into my first teaching position at Rutgers University, I read my second Toni Morrison novel which had just come out: Beloved. My research interests began to narrow in 1989, as I presented two successful conference presentations and published an article on Beloved based on them in 1995. I joined the Toni Morrison Society in 2000.

Bishop’s Restaurant, 1963. Guards barring African Americans from the cafe.

As for my girlhood: I passed through this important phase in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in the 1950’s and 60’s, when Jim Crow separate-but-equal practices were visible and enforced, until 1965 or so when Oklahoma City Board of Education Director Clara Luper took her Douglass High School students to lunch-counter sit-ins throughout the city. My neighborhood was segregated, as were church and school, until the mid-60’s, but I did have the grace to be around black Oklahoma Cityans through my maternal grandmother, Tilly Caldwell. She lived in near east Oklahoma City, which was predominantly black, and she rented the upstairs of her property to African Americans.

Anecdotes in Oklahoma City

I remember a day in the mid-1950’s when Gram was walking me and my sister to Kaiser’s ice-cream and soda shop on a hot summer afternoon. We by three little girls about our age who were jumping rope, and someone driving by yelled an ugly word at them out of a car window. “Gram” told us that if she ever heard my sister or I use that word, she would wash our mouths out with soap. When Gram died in 1965, the choir at her church service was mixed-race.

But I was also a part of the racism at that time. As a child, I watched episodes of the racist series, The Little Rascals. In my high school pep club, we learned a chant to perform at basketball or football games when the opponent team was from Douglass High School:

Pork chop, pork chop, greasy, greasy:

We’ll beat Douglass, easy, easy!

Douglas was the black high school in my town. I remember chanting this racist insult at a basketball game one time in particular. The Douglass cheerleaders across the court just stared at us. And I had to turn my eyes away from looking at them. In my memory (which I admit is unreliable), I never did use foul language to, or about, African Americans. But I failed to take action in either word or deed to protest some of my friends who did use that language.

Clara Luper, Oklahoma City 1959

My liberal Methodist Youth Fellowship sent supporting letters (unofficially) to Clara Luper and took up a collection for her students to support their lunch-counter sit-ins at the Skirvin Hotel and Anna Maude’s restaurant around 1967. When that was discovered by my church’s leaders, our teacher was “fired.”

I also served as a liason between my nearly all-white high school (Northwest Classen) and Douglass, the all-black high school under Clara Luper’s program launched in in 1968. I look back now and see how I could have done so much more to make a difference, to get to know people, and I demurred. I am more than a little ashamed of that.

Meanwhile, throughout high school, I went to rock concerts with my white girlfriends (Jerry & the Pacemakers, James Brown, the Beach Boys, Ike & Tina Turner to name a few), swam summer days away at the all-white “country club” that my parents joined in the 1960’s, and generally basked ignorantly in white privilege.

Lakeview Country Club Pool, OKC 1965. Whites only.

Looking back fifty years, I see myself as comfortably ensconced in yet discomforted by that privilege. And while I have made strides in my consciousness and actions against it, I must admit that I remain under its spell. I can only offer what I hope is a mind and emotional intelligence willing to keep working. As far as readings that have helped me, I have to mention a couple of things.

Dare I Say Awakening?

It was reading the philosophy of W.E.B. Du Bois in college that began to affect my thinking about African American portrayals in film and literature, and about performances of black musicians. Specifically, it was Du Bois’ articulation of double-consciousness. Many of you readers are familiar with this notion, and of so much philosophy that has developed from it, but I hope it is worth your reading effort to re-visit this famous passage from The Souls of Black Folk along with those of you who haven’t read it yet:

“After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, — a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Through this idea of having to look at oneself through the eyes of racist gazing, I began to pay attention to the subjectivity of African Americans. It was on my radar for good.

Another text that has made a deep imprint on me is Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo. In this novel, African Americans are “woke” while the white civilization that has prevailed for a couple of thousand years is decadent and decaying. The scene is Harlem when Herbert Hoover was elected president and “the Negro” was in vogue. “Atonists,” as Reed called the white civilizations, were dead-pan serious and mono-minded, like the Egyptian King Aton, while the African Americans like Papa LaBas were the spiritual descendants of Isis and Osiris. They were open to many different traditions, and therefore were wiser, more human, and could laugh at themselves.

Mumbo Jumbo was a watershed novel for me both personally and professionally. It framed “white privilege” for me before the term was invented. It celebrated blackness unfettered by white conventions. And it was the beginning of my interest in African American novels and novelists.

This blog grows out of a book project that was 10 years in the making, initially rejected by an academic press editor. This editor had sent it to an ethnomusicologist, who wrote in the review: “this kind of book should not be written.” My work to combine the vocabulary of a Blues/Jazz African American musical aesthetic with the vocabulary of the art of narrative so as to describe the effects of Toni Morrison’s narrative art on readers was categorically rejected, and my musical knowledge critiqued. I went back to the “drawing board,” so to speak, spending several years learning more about jazz through jazz musician (bass) and teacher Karyn Quinn, reading, listening, and tapping.

I readily admit that I will never qualify as a music critic; I do qualify as a literary one. Still, I have not deviated from my decades-old argument that Toni Morrison’s work is profoundly intermedial While is it primarily written art, it is has musical and painterly components. And so I write.

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post:

Do you have a response, positive, negative, ambivalent, etc., to my autobiographical posting here? Or how would you outline your autobiographical intersections?

From here? Go wherever the mood takes you. But if you haven’t encountered the one unclassified blog yet, which is a sort of summary, then you might like that: