”More Work, Down Here in Paradise”: Backframing the Beloved Trilogy

Gulf Islands National Sea Shore

Just as the sea’s rhythmic waves refresh two exhausted figures lying together on a seashore in the epilogue to Paradise, they wash over us as well, as we’re finishing not only an unresolved-but-hopeful novel, but an unresolved-but-hopeful trilogy.

My chosen language, “unresolved-but-hopeful” was not chosen to be glib; nor am I lazy in grabbing at what might seem a cliche. Perhaps I am soothed by Morrison’s beautiful aural accents and generative descriptions on this last page, for I do not want to use words like “tragic,” “violent,” “abandoned,” “orphaned,” “heartbroken”; even though these words, too, describe some of my emotional reflections on the figures in these novels.

Spoiler Alert: this blog concerns endings of the novels. Save this for later if you don’t want to think about the endings now . . .

1. How might the last page of Paradise offer us a “coda”: some contexts through which we can reflect upon the trilogy as a whole? Let’s review the opening of Beloved as we think about this.

2. How do you see the barefoot walking motif—one episode of it early in Beloved, the other late in Paradise—as a significant framing device for the trilogy?

3. At the end of the trilogy: where do we, you and I, go from here?

Paradise’s Last Page and a “ReCall” to the opening of Beloved

Let’s review a little: the Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise trilogy opens in the first pages of Beloved with a scene of fragile stability, a long ebb-tide after some as yet unrevealed dramatic events: there is a house, haunted by a baby’s angry ghost. The current residents of 124 Bluestone Road on the outskirts of Cincinnati have dwindled down to 2. There is an aura of resignation in the telling, which describes how others have left over a number of years; with the passing of the matriarch, Baby Suggs, followed sometime later by the leave-taking of baby-ghost’s two brothers, who walked away one day with no sign of ever coming back.

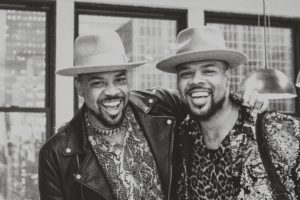

malcolm garret \Pexels

The reader is stumped by this opening since many of the orienting details of time, place, and characters—alive and dead, present or absent—are withheld. Awash in this ebb-tide, we readers anxiously await something. And eventually, we go forward in the “current” time of this story setting, and then we go backward as well, to recover the past events, in an alternating rhythm that is largely controlled by subjective, internal dramas of remembering and forgetting, both of which take on an almost uncanny importance in the special chronotopes, or timespaces, in Beloved.

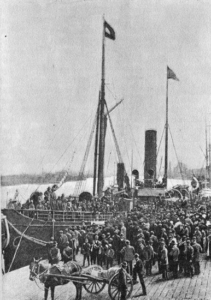

The Trilogy Ends with a Ship Coming to Shore

Back to Africa: the Horsa, bound for Liberia from Arkansas, 1895. Courtesy of /Smithsonian originally published in Harper’s Weekly

The trilogy ends with the otherworldly timespace of Paradise’s short epilogue, the setting being a seashore with a ship coming in loaded with tired and disgruntled passengers. Two women, one with “tea-colored hair” cradled by another, “black as firewood,” rest on the sandy shore, before they will rise and again “shoulder the endless work . . . down here in paradise.” These two women on the sand recall characters in Paradise: the orphaned Brazilian, Consolata, who became a healer for an all black community in the American West; and the other a syncretic mix of Consolata’s guardian, Mary Magna, and a Black Madonna figure. Their restful state will only be temporary, however, as here comes more people “ashore,” a never-ending cycle.

Paradise’s epilogue provides a coda for the effort—not the accomplishment—of achieving a utopian homepage. It does not offer a clear way out of the constant work of balancing the desires to both remember and forget and to be both safely confined and dangerously free, and it does not completely resolve issues of retribution or forgiveness. Instead, what the final geography of Paradise’s “going home”-page offers is a timeless solace while the work continues. After all, as I read this last page, the words of Billie Delia just a few pages earlier are still ringing in my head:

When will they [the Convent women]reappear, with blazing eyes, war paint and huge hands to rip up and stomp down this prison calling itself a town . . . a backward noplace ruled by men whose power to control was out of control and who had the nerve to say who could live and who not and where. . . . She hoped with all her heart that the women were out there, darkly burnished, biding their time, brass-metalling their nails, filing their incisors–but out there (308).

Annie Spratt /unsplash

Yeah!

The work of building a safe African-American community–in which all, not just some–may flourish will go on. There will be more hauntings from the past in other houses, as with 124 Bluestone Road, but there will be the beauty of trees, bare feet, 40-mile women and walking men in whose company you can cry; all rendered in the stunning language and rhythm of Morrison’s Black Musical Vernacular, a textuality that wants to hold your, the reader’s, hand.

This is the crux of Morrison’s project, which began about “love” but became much more historical about Black life in the United States in the process: imaginary chronotopic timespaces through which readers all over the world can enter and then hold on to that experience; making some impact, having some effect, on our own emotional intelligences.

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post:

In Paradise’s Epilogue, there is also Morrison’s final Call to Readers of her trilogy: “Sending rhythms of water ashore.” How do you, as a reader of Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise, feel about it all, here at the end? If the words “emotional intelligence” click with you, write about how your emotional intelligence has been affected.

“Barefeet and Chamomile Sap”: the path leading to A Mercy.

In his conclusion to What Else But Love? The Ordeal of Race in Faulkner and Morrison, Philip Weinstein states that the reason for Toni Morrison’s popularity “is her refreshing capacity to narrate human behavior calibrated upon something other than a capitalist model of consumption, exchange, and individual empowerment” (190). There is a specific walking motif, a repetition-with-difference, that captures for me that “something other” upon which human behavior can be calibrated, and it actually frames the trilogy. . . Or rather backframes it.

I say “backframes,” because only near the end of Paradise’s story structure (before the epilogue page), while absorbing a barefoot-walking episode, do I realize that there was another barefoot-walking episode in the opening pages of Beloved. For me, these two scenes frame the trilogy, and they comprise a significant repetition-with-difference.

“Walk worthy.” Ephesians 4:1-3

Starting with the end: the last walker to be narrated in the trilogy is Deacon Morgan in Paradise, fully-suited but barefoot, making his way to his minister’s house. He simply could not put on his shoes and socks that morning. “I got a long way to go, Reverend” (303), he tells Baptist Minister, Richard Misner, one month after his participation in the shooting of the women at the Convent. He is ashamed of his and his brother, Steward’s, violence against females, and makes a public walk four blocks down Central Avenue in Ruby (from St John past St. Luke, Cross Mark, St. Matthew, and down Cross Peter), stiffly greeting friends along the way to make a confession of sorts.

Deek separates himself from the “controlling story” of his forbears in order to live forward, rather than backward, in time. Like David making his way up the Mount of Olives, barefoot and weeping (2 Samuel, 15:30), Deek makes his humbling, barefoot walk down Central. His “long remorse was at having become what the Old Fathers cursed: the kind of man who set himself up to judge, rout and even destroy the needy, the defenseless, the different” (302), and it suggests the possibility of other Rubyites responding similarly.

In contrast to Deacon’s barefoot walk on a hot September day down a paved road through the center of Ruby, Oklahoma (1970’s) is Sethe’s barefoot walk through a breezy, green field on her way back to 124 Bluestone Road on the outskirts of Cincinnati (1870’s). Sethe decides to go barefoot across a field, but the chamomile sap stings her legs so much that she runs to wash them off at the water-pump behind the house. Standing there, shoes and stockings flung on the ground, she suddenly remembers. “Then something. The plash of water . . . And suddenly there was Sweet Home rolling, rolling rolling out before her eyes” (7).

Harrison Haines /Pexels

Memories of the plantation where she was a slave, mixed-up sensations of pretty trees and dead bodies hanging from them, a memory for which she could not forgive herself. But: rounding to the front of 124 Bluestone on her cleaned bare feet, she encounters Paul D, another former slave whom she had not seen in 18 years. The moment is charming to Paul D, and he, too, takes off his shoes as they sit on the porch together and talk.

Both barefoot sequences are about disarming in several senses of that word. To go barefoot deprives one of the means of attack or defense; it is a figurative laying down of one’s weapons. Lay it all down, as Baby Suggs advised Sethe, and study war no more (Beloved 86). That is what the resentful women finally did when they went to Sethe’s house and, “voice upon voice,” drove the “devil-child” from her midst (Beloved 261); what Violet, Joe, Golden Gray, Malvonne, and Dorcas finally managed to do; and what Deek was beginning to do. Paul D, laying down his own resentment and pride and returning to Sethe at the end of Beloved, sang it:

Bare feet and chamomile sap.

Took off my shoes, took off my hat.

Bare feet and chamomile sap

Gimmie back my shoes; gimme back my hat.

Lay my head on a potato sack,

Devil sneak up behind my back.

Steam engine got a lonesome whine;

Love that woman till you go stone blind.

Stone blind; stone blind.

Sweet Home gal make you lose your mind.

–Beloved (263)

Ronnie Overhate /Pixabay

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post:

What do think about “barefoot” as a metaphor in a general sense, and then as it is developed by Morrison? (You might want to recall the discussions of a range of walking motifs in the blogpiece “At the Bottom of the Band”).

Opportunity to bring in A Mercy:

You might also want to write about Florins in A Mercy, if you have read that novel. Recall that Florins has no boots (Malik took them, she thinks) as she makes the long trek back to Rebecca Vaark’s farm after the rejection by, and her pummeling of, the blacksmith with whom she was so smitten.

At the end of the trilogy: where do we go from here?

Morrison has stated about the endings to her novels: “People complain about my endings, because it looks like they are falling apart. But something important has happened; some knowledge is there . . . . . I don’t shut doors at the end of books. . . . . Suffering is not just anxiety. It is also information.” And that information, Morrison states, must, “like black music . . . never fully satisfy.” (Bessie Jones & Audrey Vinson, “An Interview with Toni Morrison”).

I think of it this way: there will always be a remainder, like the “sea trash” at the end of Paradise: bottle caps, a sandal, and a “dead radio” (318). This is also tied into the Blues-Durative structure of the three novels (see my blogpiece, “Roots of Toni Morrison’s Durative Blues” LINK). In blues literature critic Toni Bolden’s words, “the blues tradition narrates the subsequent dialectical interchanges between colonizer and colonized, theft, exploitation, and (re)creation in a drama without closure” (Bolden 38). “Without closure” is an appropriate transition to the further explorations of Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise.

brittanica.com

Lastly, in the preface to Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, Morrison writes that “the imagination that produces work which bears and invites rereading, which motions to future readings as well as contemporary ones, implies a shareable world and an endlessly flexible language” (xii). The level of Toni Morrison’s mastery with language–the aural accents, generative descriptions, call-and-response, to name but a few– guarantees that there will be infinite opportunities for readers present and future to plunge into the Beloved, Jazz, an Paradise trilogy, like into a great sea, surfacing for air with exhaustion but also refreshment, resting for some time on shore, until we rise again, “unresolved but hopeful.”

Peace be with us all!

If you’ve finished the Root Blogs Cluster, I suggest going on the Readers Cluster with There is Sound in My Works.

And do sign up for the Newsletter if you have not already. Just go to the bottom of any page.