Black Mappings

“Black geographies allow us to consider alternative ways of imagining the world.”

–Katherine McKittrick & Clyde Woods, Black Geographies and the Politics of Place

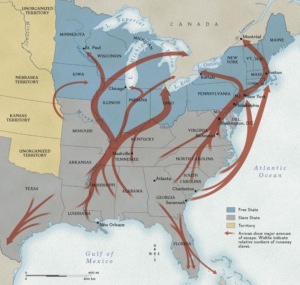

Consider the historical “Underground Railroad”: that vast network of people and places in the United States that aided runaway slaves on their journeys to free states and Canada in the 19th century.

Native Tribes Map /National Geographic Society Map

For many African-Americans in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, these trajectories towards freedom were known in concrete ways. Meet in the farthest corn; get off the wagon at the shack with a white cloth tied to the fence; walk miles to the river; wait by the split oak tree . . . Today, you and I can visit some “stations” of the underground railroad: walk through damp underground tunnels (Middleton, Wisconsin), peek into cobwebbed attics (Oberlin, Ohio), read plaques about who was there (northern Kentucky: Margaret Garner). But our mappings of the United States have remained generally unchanged by these routes or any migratory movements, for that matter, even the Native peoples who were torn from their lands and “removed” into smaller and smaller spaces for annihilation. (See Demonic Grounds)

Maps of Black American Presence

This blog focuses on maps, both static and dynamic, that have rendered African American lives visible. It will address the following query:

What are some of these historically identified maps of Black American presence in the U.S.? Are these maps static or dynamic?

Let’s return to the historical demographics of Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise that I discussed in Morrison’s Beloved Trilogy, those diasporic exiles and migrations:

Harvard College Library

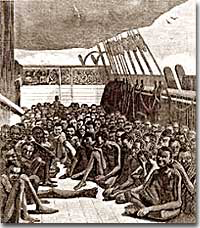

The Middle Passage—taken from their homes, bound on ships from Africa to the Americas, to become slaves (Beloved)The Underground Railroad—escaping slavery, sometimes given aid along the way, going north (Beloved)

The Great Migration—traveling by train, car, and on foot from the south to northern urban cities for better opportunities (Jazz)

brittanica.com

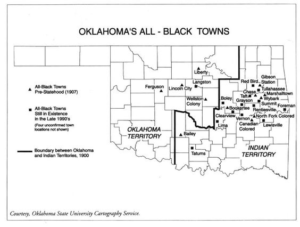

The All-black towns in the West—from Mississippi and Louisiana to Kansas and the Oklahoma and Indian Territories to claim land ownership and forge self-sufficient all-black communities (Paradise).

Maps are ingenious documents that both reveal and conceal information and ideology. Following Katherine McKittrick’s and Paul Turchi’s lines of thought, I would also venture to argue that maps—in their production and reception—are products of our emotions. As an example, I will use my own reactions to reading Toni Morrison’s Paradise. If I had not read it, I doubt if I ever would have come across this map.

I grew up in Oklahoma (1950-1974), and yet knew only one of these towns,—Langston— existed! It took reading Paradise in 1998 for me to realize that I needed to do historical research. Estimates of the numbers of these all-black, self-sufficient communities vary, but there were around three dozen of them. Few white Oklahomans today seem to know the extent of this amazing network of towns that thrived from around 1890 to 1920. When I realized the actual material presence of towns such as Boley, Clearview, North Fork Colored, Tatums, and so many more, less than a half-day’s (or even just 1 hour’s drive) from my hometown of Oklahoma City, I thought I had stumbled onto a long lost, secret world.

And in a way, I did. I still have few words to describe my feelings at the time. So much life had been concealed, erased, silenced, stilled, by the dominant “history” of Oklahoma as the boomer-sooner state, the land-runs celebrated as the root of Oklahoma’s (white) identity. However, there is the acknowledgement of the prior period: the “Five Civilized Tribes” that had been removed to Indian Territory from the southeast. That was too national a scandal to be thoroughly erased. Now, Indian history in Oklahoma is being written afresh; for example, both the novel by Linda Hogan, Mean Spirit and the non-fiction historical narrative. The Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann, reveal the history of the swindling and murdering of Osage Indians in the 1920’s and 30’s.

Paradise is centered on some of the Black-Town history, and, typically for Toni Morrison, in iconoclastic ways. See my blog on The Puzzling Chronotope of Oklahoma (coming soon!) for more discussion about Black Mappings in Toni Morrison’s work.

Finally, I’ll leave you with one more statement by Katherine McKittrick before the Responses Invitation:

“In the production of black geographies, a “tension, between the mapped and unknown, reconfigures knowledge, suggesting that places, experiences, histories and people that no one knows do exist, within our present geographic order”(4).

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post:

What are some of the ways in which reading a Morrison novel—any one of them—has impacted your sense of African American geographical presence in this land?

Next up in this blog cluster: Baby Sugg’s Hands and the Ungeographic.

And please sign up for the Newsletter in the space at the bottom of the page!