Claiming Geographic Space

“Winging one’s way through the vise and expulsion of history becomes possible in creative encounters with that history.”

—Toni Morrison

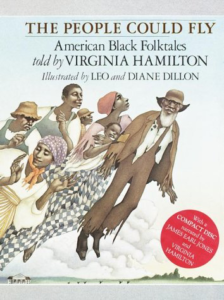

The folklore of the flying Africans is a creative response to exile and captivity. “The people could fly. They flew like blackbirds up above with their wings shining against the blue sky,” the story begins in Virginia Hamilton’s rendering in the book above (with amazing illustrations by Leo and Diane Dillon). Apparently, some people, after their arduous trip to the Americas in the hulls of slave ships, remembering that they could fly, did so. The origin of the story is thought to be rooted in an actual overthrow of a slave ship by an Igbo group from Nigeria who, when landing in South Carolina, jumped into the river and either drowned or flew away, depending on the teller.

The Centrality of Geographies in Morrison’s Trilogy

Variations were told and retold throughout the nineteenth century. In fact, many Americans interviewed in the 1930’s through the Federal Writers’ Project would say something like, “I didn’t see it, but I know so-and-so, a lady down the road who did.” What a powerful tale for people who were forced to venture into unknown and hostile terrain! But the metaphor is more: it is the origin of creating black geographic space in a world where African Americans have been rendered “ungeographic.”1 This is a new word for me, as well as perhaps for you. But I think it makes sense; read on to the next blog in this section, Demonic Grounds, to see if you agree.

Nigam Machchhar /Pexels

Actually, in Toni Morrison’s 3rd novel, Song of Solomon, there are direct allusions to the Flying African tale. One is at the end of the novel where a character nicknamed Milkman—living in the 1940’s— is finally able to transcend his self-centeredness and confront a deadly threat from his friend by jumping blindly off a bluff. “For now he knew . . . that if you surrendered to the air, you could ride it” (Song of Solomon). The notion that one will have to step into the unknown with a leap of blind faith in order to have the chance to survive and thrive takes on dramatic significance in Beloved, Jazz and Paradise. (There are about 1/2 dozen blogpieces in this Claiming Geographic Space blog cluster, some argumentative–Black Mappings–some expressive–Slave Ship Geography–and much more.)

The Building Blocks of Eventfulness

Stockpik /Pixabay

How do story structures develop and organize emotional experiences?

At the risk of stating the obvious, through space and time. Story-worlds are, like our own life-patterns, dependent on places and temporal sequences. The time-spaces, or chronotopes, created in Morrison’s works create large political questions about the American geographical imagination as well as perceptive meditations on the body, especially the enslaved body, as a significant geographical marking. This blog pairs with another, “Demonic Grounds,” to ferret out a fresh, new perspective on Morrison’s work in terms of people claiming their geographic identities.

Morrison’s exploration of the geographic ontologies of African America in her Beloved Trilogy covers a range: from large “mappings,” such as the spatially-oriented map of the United States, to small ones, such as personal ownership of one’s own body. In Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer, Peter Turchi develops a set of ideas about mental mappings along side historical mappings. We have a “premapping” framework in our cognitive structures: “the desire, and so the attempt, to locate ourself” (28).[ Turchi, Peter. Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer. San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2004.] If you’ve read the piece, Emotional Story Structures, you’ll recall Patrick Hogan’s work on affective science and literature here. Our emotions are tied to time and place, actual or imaginary. So we have emotional mappings, in Turchi’s sense, in relation to geography. Where have we lived? Where is “home” and “away”? What are our favorite places, scary spaces?

Imagining Freedom

Jessica Felicio /Unsplash

The folklore of the flying Africans is, in an important way, concerned with mental mappings. It boldly imagines the freedom to go home to Africa and the freedom to fly out of a terrible bondage. These folktales also initiate an artistic practice of creating and declaring geographic relevancy in order to confound and transgress the dominant culture’s restrictions on the status of Africans brought to the Americas to be slaves.

Toni Morrison’s work in general can be seen as a project in geographical remapping, but it is with the Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise project where creating geographic space and time becomes inextricably linked with the trilogy’s emotional trajectories of love and memory” exile, migration, non-belonging, home. So what I want you to consider with me is how Toni Morrison’s love project developed into a geopolitical project as well as she worked on the novels from the mid-80’s through the mid-90’s.

Most significantly for thinking about the geographical dimensions of Toni Morrison’s trilogy,

what maps are created by the stories contained in Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise, and how might the mental maps of readers be altered by them?

If, as Turchi argues, “our sense of a place is in many ways more important than objective fact” (28), then it’s possible that the mappings in Morrison’s work will impact our own mappings. Whether on the broad scale—a greater sense of North America’s African presence across exiles and migrations—or the more intimate scale–how might it feel to experience freedom for a former slave woman who questions out loud: “these my hands”? ( see the piece on Baby Suggs’ Hands), the trilogy’s geographies can help us experience race outside of the “lethal cling” of racism. Let’s put that on our maps.

Responses Invitation: reflect, write post:

We can all think of special locations and landmarks from our experiences that figure prominently in our mental mappings; a grandparent’s old house, a swimming hole, dance room, bus trip, city square or mountainside. But what about your imaginary experience with place, especially place infused in some way with African American presences? In what ways have books, films, plays, or musical works affected your mental mappings of space and place to include African American lives? Pick an example—book, film, play, album, concert—and discuss how this artistic work has expanded your mental mappings of space and place, either local, national, global, etc.

Continuing with the Geographic, I suggest you go to Demonic Grounds: Morrison’s Literary Chrontopes.

Please sign up for the Newsletter at the bottom of the page!

1 In Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, Katherine McKittrick traces how imperialist geography, “white masculine European mappings, explorations, and conquests,” has rendered the colonized subject as “ungeographic” (McKittrick xxi).