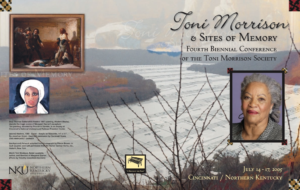

Does Toni Morrison Write “Mixed-Media” Novels?

Northern Kentucky University

“I thought of myself as like the jazz musician—someone who practices and practices and practices in order to be able to invent and to make his art look effortless and graceful. . . . When Keith Jarret plays “Ol’ Man River,” the delight and satisfaction is not so much in the melody itself but in recognizing it when it surfaces and when it is hidden, and when it goes away completely, what is put in its place. Not so much in the original line as in all the echoes and shades and turns and pivots Jarret plays around it.” –Toni Morrison, Paris Review

When I first read Morrison’s words on Keith Jarret’s jazz performance several years ago, I leapt on that language because it opened something up for me: it described some aspects of how I experience reading some of Toni Morrison’s novels:

–Like those sequences where the story of the “crawling already?” baby in Beloved surfaces, and then sequences which obstruct it but it’s there, beneath the surface.

–As when in Jazz the narrative of “Golden Gray” surfaces, and when it seems to “bleed” into other sequences (metalepsis) such as into some of Violet’s and Joe’s separate thoughts (which is ironic since neither knows the other knew Golden Gray in any way).

“Risky, I’d Say”

Citing musicality in a literary text is risky, and for good reason. Beyond explicit, overt references to music—songs, musicians, instruments, singing, etc.—a story or poem might seem musical to readers in a broadly impressionistic, affective way. But that isn’t yet evidence of true intermediality: “the identifiable participation of two or more media in a single artifact.” This is the definition that Werner Wolff offers in his work, The Musicalization of Fiction: A Study in the Theory and History of Intermediality, for works of literature that, in some key aspects of structure and style, resemble music.

I may be sticking my proverbial neck out here when I suggest that it is no coincidence that Morrison’s interests in doing “something like” the music used to do for African Americans–as evidenced in essays, interviews, and the like–span the years during which she was writing Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise.

But how effective are an artists’s comments for their audiences’ experiences of their work? Will readers, guided by these commentaries, be able to identify musical elements? How will these elements impact readers? These are questions to be addressed in this blog, with your help!

Romare Bearden, Duke Ellington, Toni Morrison: Intermedial Artists

Artists frequently talk about what they are trying to do in their work. They want to offer their viewers, listeners, or readers some clear directions for what to look for in experiencing their art forms. While this type of evidence does not constitute proof that their works do what their creators say, it is nevertheless compelling.

Mill Hand’s Lunch Bucket by Romare Bearded

American painter Romare Bearden says this about jazz music’s influence on his painting: that listening to jazz “helped him make use of the spaces between the shapes” in his paintings.

Bearden defines his work in terms of rhythm, spacing, and “tonal” use of color. Here is his description of his creative process: “I take a sheet of paper and just make lines while I listen to [jazz] records. A kind of shorthand to pick up the rhythm and intervals.” (Diedra Harris-Kelly, “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation” in Robert O’Meally’s Uptown Conversations, 249-55)

And then there is the matter of Duke Ellington’s definition of “paralleling” other media in his music. In his autobiography, Music is My Mistress, the Duke describes his 1943 jazz symphony Black, Brown, and Beige as a “tone parallel to the history of the American Negro.”

Duke Ellington Orchestra

Ellington along with Billy Strayhorn attempted to parallel Shakespeare in Such Sweet Thunder, the “Shakespearean Suite,” that was created around characters of Othello, Henry V, Lady Macbeth, Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Romeo and Juliet at the 1957 Stratford, Ontario Shakespeare Festival. But besides the efforts of representational paralleling, there are also instances of structural paralleling, as with the “Sonnets” that employed 14 phrases of 10 notes each, musically incorporating the literary sonnet form.

Toni Morrison also suggests that there can be identifiable evidence of musicality in literature:

Classical music satisfies and closes. Black music does not do that. Jazz always keeps you on the edge. There is no final chord. There may be a long chord, but no final chord. And it agitates you. Spirituals agitate you, no matter what they are saying about how it is all going to be. There is always something else that you want from the music. I want my books to be like that—because I want that feeling of something held in reserve and the sense that there is more—that you can’t have it all right now. . . .

So structurally, Morrison is suggesting, a novel can parallel a jazz score in which there is no final chord, there is something held back, and so forth. (We will examine the structural paralleling of jazz in Morrison’s prose further in View From the Bottom of the Band.) Let’s consider a final point here: ethical emphasis on what black music does and whether or not that can be identified in spoken narrative. According to Bernice Johnson Reagon:

Bernice Reagon & Sweet Honey on the Rock

“Black music moves from grief to grievance.”

“Sending that sound in front of us, we could move inside it.”

“The boundary between music and literature is not porous but liquid.”

Responses Invitation: Reflect, Write, Post:

How effective are artists’ remarks in guiding readers to experience the intermedial, or mixed-media, dimensions of their work? Select any passage from one of the artists quoted above (Bearden, Ellington, Morrison, Reagan) and write about it: see if you can use it to discuss the following passage from the epilogue to Beloved.

Remembering seemed unwise. The never knew where or why she crouched, or whose was the underwater face she needed like that. Where the memory of the smile under her chin might have been and was not, a latch latched and lichen attached its apple-green bloom to the metal. What made her think her fingernails could open locks the rain rained on?

Oh, my. Let’s continue with the focus on the artist in View From the Bottom of the Band.

And do sign up for the Newsletter if you have not already. Just go to the bottom of any page.