Talking Back to Aeschylus

“But when necessity’s yoke was put upon him/ he changed, and from the heart the breath came bitter/ and sacrilegious, utterly infidel,/to warp a will now to be stopped at nothing.” –Aeschylus, The Agamemnon

Morrison’s art of the novel is rich with intertextual references to other works of literature. There are several excellent studies you may know already on Morrison and Faulkner. And there is a recently published book on Morrison and Classical literature (Tessa Roynon, Toni Morrison and the Classical Tradition: Transforming American Culture).

In this blog, we will explore the ways in which Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise make a striking comparison to that ancient Greek dramatist Aeschylus’s trilogy, The Oresteia, and particularly with its first play, The Agamemnon. And by the way, you do not have to go read Aeschylean drama in order to have an adventuresome reading experience with this blog!

Morrison’s Parallels with Aeschylus

First of all, as with the three tragedies of Aeschylus, each of the killing scenes in Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise forms the dramatic emotional story structure of its respective novel around which much mystery, anticipation, dread, and other textual energies circulate. Another aspect of Morrison’s project which is similar to Greek lyric tragedy is the tracing of causality from generation to generation. Classical Greek drama, according to scholars, has the capacity to bring past events and future forecasts into the present time of the dramatic action, a “dilation or thickening of the tragic moment and enormous buildup of tension around it.”2

In the Oresteia, there is a marked repetition of the temperaments of mourning and retribution among several generations of the “house of Atreus.” While Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise do not explicitly trace several generations of one family, they do accent the repetition of character traits in such a way as to suggest a kind of metaphysical reincarnation. Not only does the “woman black as firewood” in Paradise (318) has her antecedents in Beloved (Beloved) and Wild (Jazz), but Sethe and Paul D (Beloved) seem reconfigured into Joe and Violet (Jazz) and Connie and Deke (Paradise).

The actions of characters are shown to reverberate from one novel to the next, just as in Aeschylus’ trilogy, for they share a common struggle, or in the Aristolean sense, agon. Let’s drill down, now, to specific elements of Morrison’s and Aeschylus’ emotional story structures.

Pain and Knowledge

Wallace Chuck /Pexels

The truth

Has to be melted out of our stubborn lives

By suffering.

Nothing speaks the truth,

Nothing tells us how things really are,

Nothing forces us to know

What we do not want to know

Except pain.

And this is how the Gods declare their love.

—Aeschylus, The Agamemnon, trans. Ted Hughes

Suffering, in Greek, is pathei mathos: it is a term that indicates a certain kind of knowledge that comes from emotional intelligence. In The Fragility of Goodness, philosopher Martha Nussbaum notes that pathei mathos does not indicate merely an intellectual understanding that comes from suffering; rather, the phrase designates “an occasion for an activity of knowing that could not even in principle be had by the intellect alone” (Nussbaum 46). Furthermore, the audience must experience pity in order to gain a measure of the same emotional knowledge of human experience that the actors gain.

Morrison’s version of pathei mathos in Beloved emphasizes the innate value of emotional suffering by initiating—though not completing—redemptive journeys for her characters Sethe, Denver, and Paul D. Their capacities for the recognition of their own neediness—as well as their self-loving acceptance of it— increase in the course of the story.

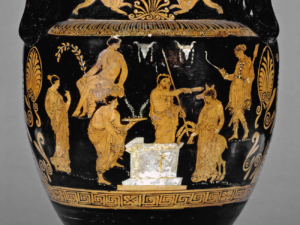

Volute krater detail depicting the sacrifice of Iphigenia, 370-350 B.C. The British Museum /Creative Commons

Aeschylus’ philos-aphilos or “hate-in-love” theme, concerning how these two forces collide in individuals and force some “distorted action . . . against a part of themselves so that what they kill is what they love” (Lattimore edition), resonates with Sethe’s killing of her baby girl in Beloved, Joe’s shooting of Dorcas in Jazz, and the Ruby patriarchs’ murders of the women at the Convent in Paradise.

Morrison’s novels also share with Aeschylus’ lyric tragedies a telling of, and choral mourning for, the vagaries of the human emotions. Agamemnon’s bold sacrifice of his daughter and Clytaemnestra’s revenge as presented in The Agamemnon can be aligned with Sethe’s and Beloved’s struggle in Beloved. And the deliberative philos-aphilos, or love-in-hate struggle, of Orestes concerning his mother Clytaemnestra in Libation-Bearers bears a resemblance to Joe Trace’s emotional entanglement with Wild and Dorcas in Jazz.

Third, the civic judgments of Pallas Athena in The Eumenides to make a place for the Furies in the new city is similar to the notion that the murdered women from the Convent will return, “brass-metalling their nails” (Paradise) to keep the controlling men from going out of control in Paradise.

Nails by Saab

Actually, Morrison and the known Greek tragic playwrights–Sophocles and Euripides as well as Aeschylus–share fundamental concerns for divine justice in this world and for the central role played by human emotions in the search for justice and truth. Exemplary themes in this area are: the dangers of pride and selfishness, the unpredictability of desire and neediness–erotic, maternal, infantile, etc.–and the importance of honoring all the gods: Dionysus as well as Athena and Apollo; gnostic female revealers (“The Thunder, Perfect Mind” in the Egyptian Nag Hammadi collection, from which Morrison draws the epigraphs for both Jazz and Paradise); as well as Hebrew and Christian prophets.

Outcomes Fall Short of Expectations

Morrison’s Beloved trilogy and Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy contain elements which resonate with Trudier Harris’ description of African American folklore “in which outcomes fall short of expectations,” (Harris 11). Joe’s need to work himself up to be able to shoot Dorcas in Jazz could be aligned with Orestes’ drawn-out effort to steel himself in order to kill his mother in Libation Bearers. Joe’s actions are examples of philos-aphilos, or love-in-hate struggles. In fact, Lattimore’s comments on The Libation Bearers apply well to Jazz: the play “is only superficially a drama of intrigue . . . [t]he emphasis lies on the mood in which the characters act” (Lattimore 26). The moods of the characters are foregrounded in Jazz, by the music and the desire of the 1920’s in the City.

Finally, the Eumenidies, or the Eryines, as Aeschylus’ third play of the set is sometimes known, has some parallel emotional story structures to Paradise. Athena will let justice prevail over blood-vengeance, so Orestes is saved, but she will assign the group of women who want vengeance to stay close to the Athenians, in an underground space, to assure some balance of the emotions.

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post :

Morrison’s trilogy is much more “loose” in historical chronology than is Aeschylus’ trilogy, spanning more than a hundred years in seemingly unrelated sets of characters and places. So how do you see Morrison working with some of the classical themes: suffering brings knowledge, and pain is passed down through generations?

Morrison’s work will truly ‘go down in history’ with the greatest writers we celebrate today. So here’s another twist to Morrison’s possible intertextual playing ground: James Joyce (Yes, Oh, yes, I said yes): “Human, All too Human”: Jazz’ s Narrator and Joyce’s Molly Bloom.

1 Nussbaum notes that the classical Greek tragedians (“the poets” in contrast to the philosophers) had a “profound” disagreement with Plato in this regard. They believed that suffering was “a constituent of the characters’ correct understanding of his situation as a human being” (Fragility 45).

2 Otis Brooks, p. 13. He is also citing two other sources here: Bruno Snell, Aischylos und dan Handeln im Drama, Philolgus Supplement-band 20, 1 (Leipzig, 1920) and Jaqueline do Romilly, Time in Greek Tragedy (Ithaca, 1968).