Toni Morrison’s Rhythmic Geographies: The Walking Men

Danny Glover /Earthsea

Walking figures form a prominent motifs in Morrison’s trilogy. There are many figures who are on treks, from the first few pages of Beloved (Sethe through the field of chamomile; Paul D across the country) through the story-endings of Paradise (Pallas’ ghostly figure float-walking through the walls of her mother’s house; Deacon Morgan’s barefoot walk to see the Baptist Minister). These footsteps mark “demonic ground” in creating geographies resistant to the erasure of black presences; they also mark Morrison’s black musicality.

Questions to open up some paths for exploration:

What is it about footprints, walking, trekking and tracking (and bare feet) that appeals to Morrison for developing motifs within—and across—the 3 novels?

In each novel of the trilogy, where are we readers likely to encounter repetitions-with-difference concerning walking, and how can we describe the aesthetic pleasure—the recognition that “here it is again only different!” or “how did she come up with that combination”?

Why walking?

Images, scenes of walking contribute to the emotional story structures in the novels with literally moving things along: people needing to get somewhere, wanting to get away from somewhere. Walking evokes Diaspora, as tens of thousands of African Americans travelled by foot across the country to northern and western geographies to assert freedom and independence. But walking may be a way to live the jazz life as well. Movement of the body: for some black people, jazz meant claiming their own bodies. What that must have meant for people whose bodies had been owned, who had been slaves as children, or who remembered their parents being slaves.

Then there are otherworldly figures who “walk” in some spiritual sense, also evocative of emotional, subjective experiences relating to exile, migration, and traces of ancestors through time. The function or role of this imagery repeated, then, is to connect people across time and space, evoking flow, flux, change: making freedom in freeing time, so that past, present, and future mingle and flow.

Cynthia Erivo, Harriet Tubman. Photo by Glen Wilson /Focus Features

Scattered through the Diaspora in Beloved

One of the “instruments” of Morrison’s jazz-playing is description, especially the kind in which the imagery strongly evokes action, causation, or consequence. This is the case with some of the end-scenes in Beloved. When the girl who is called Beloved, 18 years old and pregnant, thinks she is seeing her mother-woman (Sethe) abandoning her again1 as Sethe is running towards an approaching wagon with a knife in her hand (a repetition-with-difference to the shed scene), she disappears from Sethe’s front porch and runs into the woods:

“Down by the stream in back of 124 Bluestone Road her footprints come and go, come and go. They are so familiar. Should a child, an adult place his feet in them, they will fit. Try them out and they disappear again as though nobody ever walked there.”(Beloved 275; the footprints are discussed at length in the blog Some Genesis Time: The Epilogues Framing Morrison’s Trilogy).

Beloved’s footprints launch a repetition across three novels; see the sections below on Jazz and Paradise.

Another walking-motif in Beloved is the trek. Sethe escapes the Kentucky plantation barefoot and very pregnant, and walks, then crawls, for days on feet so swollen that they looked like “loaves” before reaching the Ohio river. Paul D, also escaped from that same plantation and later from a chain gang, walks north to Delaware after the war ends, guided by an Indian who told him to “follow the blossoms” to keep true north. Paul D walks again decades later, to the house near Cincinnati hoping to find Sethe (he does) and her mother-in-law, Baby Suggs (she died).

“Without a Trace” in Jazz

In the second paragraph of Jazz (2nd novel of trilogy), we get the image, rather brief, of Violet’s fleeting footprints in the “windswept” (Jazz 5) snow on the streets of 1920’s Harlem as she is returning home after making an astonishingly dramatic appearance at the funeral of her husband’s young mistress (stabbing the dead girl with a knife, but with a tone rather like what you might hear in a blues lyric of that time). And there are more footprints to come later in the novel, where they intersect with another variation on the footsteps-walking spectrum: tracking.

As Jazz’s readers, we encounter two concurrently narrated yet distinct episodes concerning Joe Trace (Violet’s husband, Dorcas’ lover) and his tracking of two women who have left/abandoned him. One episode is a flash back in time, as the young man Joe, living in rural Virginia (late-19th century), tracks the footprints of his alleged mother, “a wild woman who lived in the woods.”

Shelley Powers /Flickr

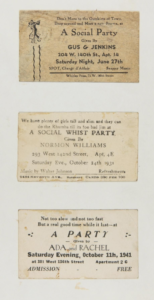

Then we encounter another tracking, decades later in time but somehow brought about by a parallel remembering of the Virginia tracking. This one is in the streets of Harlem, after lover Dorcas leaves him for a younger man, “Acton” (aptly named to denote vigor?). Joe somehow tracks her from her last known appearance at a beauty parlor to an undisclosed apartment somewhere in Harlem where she’s dancing with her new lover at a rent party[ When people needed to pay the rent, they might throw a party, asking for cash contributions and supplying liquor and music. The term “rent party” became a descriptor for any party, with or without rent-collecting going on, but definitely with liquor and music.

Langston Hughes collection of Harlem Rent Party Invites

Joe’s trackings—he was trained early on to be an expert game hunter— are both vexed with an emotional neediness that he can barely control in the first instance, trying to get Wild to acknowledge him as her son; and that he fails altogether to control when decades later in New York he shoots Dorcas at the party.

Joe named himself “Trace” because his parents apparently “disappeared without a trace,” he heard. And he has made himself over so many times (“I’ve been a ‘New Negro’ all my life”) that he almost—but not quite—becomes a timeless entity. We will encounter three timeless, otherworldly, walkers in Paradise, though, in the next example.

“Giant’s Steps” through Paradise

Walking in Morrison’s work echoes classical roots. In the Biblical New Testament, 2nd Corinthians 5:7 reads: “For we walk by faith, not by sight.” How appropriate this is to the many references to walking in Paradise. In this last novel of the trilogy, there are frequently recurring references to walking, and in uneven repetitions. Some of these walkers are historically based, but some are from “the other side” (Beloved): perhaps ancestors of prior generations, the “recently dead”; for in the West African religious sense, that can appear to living people.

Paradise’s chronology begins when a group of 158 migrants from Mississippi and Louisiana set out, on foot, for Indian Territory in the spring of 1890. Historically, this is accurate; many large groups of people came to Oklahoma on foot as well as by train and wagon. But instead of being welcomed, they were “turned away by rich Choctaw and poor whites, chased by yard dogs, jeered at by camp prostitutes” all along the way. However, even after all that, they were “nevertheless unprepared for the aggressive discouragement they received from Negro towns already being built” (Paradise 13).

Exodusters /AAREG

Morrison, in fact, reproduces the caption which E. P. McCabe ran continually in The Langston Herald for several years in the early 1890’s: “The headline of a feature in the Herald, ‘Come Prepared or Not at All,’ could not mean them, could it?” (13). This rejection story became the primary folklore of the second generation of men, who founded a new all-black (“Ruby”) town after WWII when their first (“Haven”) had failed.

In sharp contrast to the patriarchal story of founding fathers, the women of Ruby are walking, walking, walking, away from the men. The wives of the townsmen walk the 17 miles from Ruby to the Convent—where the “wayward” women live in an old mansion donated to the Catholic Diocese to establish a school for Indian girls (also historically accurate). And their walks are saturated emotional feelings quite different from those of their husbands. Lone, the elder midwife in Paradise’s all-black towns, thinks about them as she drives away from the Convent after trying, unsuccessfully, to warn the 5 women residing there that several townsmen were planning on evicting them for influencing their own wives:

Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, 1st African American Law School University of Oklahoma /Oklahoma Historical Society

Out here in a red and gold land cut through now and then with black rock . . . out here under skies so star-packed it was disgraceful; out here where the wind handled you like a man, women dragged their sorrow up and down the road . . . . . Sweetie Fleetwood had walked it, Billie Delia too. And the girl called Seneca. Another called Mavis, Arnette, too, and more than once. . . . Soane Morgan, for instance, and once, when she was young, Connie as well. . . . . But the men never walked it; they drove it. (Paradise 270).

Responses Invitation: reflect, write, post:

All of the walking figures in the trilogy make me dizzy to think about! I want to know your responses: select one or more of the examples cited above and ponder–

–Walking and diaspora; Paul D’s walk north, “following the blossoms”; Sethe’s trek to freedom; the band of migrants walking to Oklahoma, etc.

~Walking and gender: tease out some speculations on why you think Morrison employs the walking-motifs to intensify the gender conflicts in Paradise? And artistically speaking, do you sense any rhythm, syncopation, reversal, or repetition-with-difference in the walkers in Paradise?

~Walking and spirituality: walking in the Hebraic way is to live. And in the New Testament, walking in the right way, with humility and honesty, not by cunning or craft. St Paul: to walk in faith, not by sight: 2nd Corinthians, 5-7.

This concludes for now the Music & Intermediality Blog Cluster! (if you’ve not read many others in this series, go back to the Blog Page for access).

Or continue to another cluster, small for now but very helpful for readers of Toni Morrison, no matter what your education or life-experience might be like: More on Aesthetics. The first blog in that cluster is The Black Arts Movement and Beyond.

And do sign up for the Newsletter if you have not already. Just go to the bottom of any page.