“Out Here in the Real”: Race and Response-ability

“When movements have been unable to clear the clouds, it has been the poets—no matter the medium—who have succeeded in imagining the color of the sky.” –Robyn Kelly, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

Toni Morrison celebrating her Nobel Laureate with Susan Taylor, Rita Dove, Oprah Winfrey, Angela Davis, Maya Angelou & others; Winston-Salem. Photo by Will Mcintyre/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Ima

All of Morrison’s works reflect values that have been forged through generations of African Americans since slavery began; values not only of political freedom, economic agency, and emotional flourishing, but also of the aesthetic and rhetorical means of expression. And the three novels in the trilogy offer something special: an almost uncanny composition of interconnections which surpass their thematic starting points of love and remembering and transcend their joined geographies of the African American Diaspora.

Throughout the pieces in this Voice Upon Voice blog & website, you will find many references to race matters in Morrison’s writings. In this blog, I want to cite some broad strokes in Morrison’s writing about race; secondly, reconsider the disembodied consciousnesses within her novels; and finally, invite your speculation on what it means to be an American writer of justice.

Morrison’s Broad Strokes

One of Toni Morrison’s stated aims as a writer concerns her readers’ responses to the African American gaze:

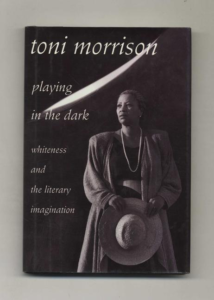

“My project is an effort to avert the critical gaze from the racial object to the racial subject; from the described and imagined to the describers and imaginers; from the serving to the served.” –Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

Bookcover: Photograph of Toni Morrison by Brian Lanker. Design Gwen Frankfeldt

Getting readers to participate in the the “making of the text” in this particular way is the important cultural work that Morrison has tried to do: to involve individuals in a collective and liberatory realignment of the margins of dominant histories and myths. And these margins and myths have to do with race. Yours, mine, ours.

Through her writing, she does show readers of any color how one can “enunciate race while depriving it of its lethal cling” (“Home”), even though she remains uncertain if her work can do so. While her recent collection of essays and speeches (The Source of Self-Regard, Alfred A. Knopf, 2019) eloquently chart the fault lines of tenacious racism perpetrated and tolerated by many Euro-Americans (known today as a collective imaginary called “white”) against African Americans, her literary work beckons readers to respond and interact emotionally with Black subjective presence in highly personal ways. “Beckons,” yes, but also demands.

“Out here in the real, sentences should be supernatural.” –Ta Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power

Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise manifest Morrison’s assertion in Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination: “Cultural identities are formed and informed by a nation’s literature.” If her work “is to confront a reality unlike that received reality of the West, it must centralize and animate information discredited by the West–discredited . . . because it is information held by discredited people, information dismissed as ‘lore’ or ‘gossip’ or ‘magic’ or ‘sentiment’” (“Memory, Creation, Writing”). From this vantage point, how one views, appropriates, and understands the past is a moral responsibility. Or, using Morrison’ emphasis, “response-ability.”

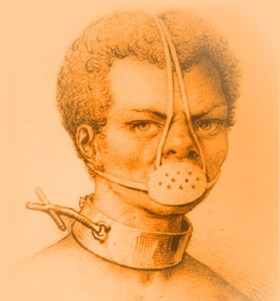

Assuming responsibility for those no one has ever assumed responsibility for: Morrison discusses moral responsibility in relation to her writing in several essays and interviews. In Marsha Jean Darling’s interview with her, “In the Realm of Responsibility,” Morrison declares that “the gap between Africa and Afro-America and the gap between the living and the dead and the gap between the past and the present does not exist. It’s bridged for us by our assuming responsibility for people no one’s ever assumed responsibility for. They are those that died en route.”

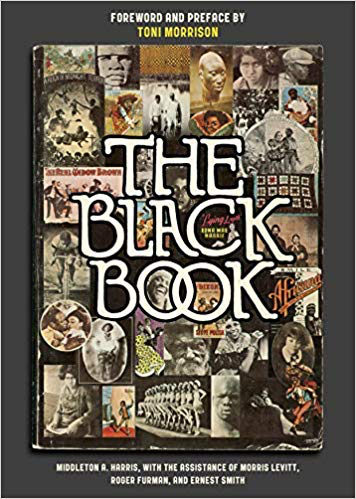

Hill Collection, Mandeville Special Collections Library, UC-San Diego

In her novels portraying African Americans in the decades beyond the slavery period, there is as well an insistent sense of recovery: of their histories, their cares, the ugliness and beauty of lived lives. And an insistent sense of the artistic freedom to render them so effectively that those fictional beings can touch the lives of readers all over the world. And although the chronotopes of Morrison’s novels are about black life centrally, there are attentions to racist goings-on at their peripheries.

Racism is described in a Beloved passage that so eloquently and definitively nails white supremacy as “the chewing laughter.” According to Stamp Paid (the character who aided Sethe’s escape and looked after Baby Suggs’ clan in Cincinnati), whites “believed that whatever the manners, under every dark skin was a jungle”. . . but even though some “coloredpeople” believed it too, the wildness or savagery was created by whites, who nurtured it until it infected them. Then, the “red gums” of the “screaming baboons” became “their own” (Beloved). Even though the dirtying done by whites on black bodies and souls (both literally and figuratively—the tree on Sethe’s back, the clabber on Halle’s face)2 is devastating, the “chewing laughter” does not destroy them. The persistent traces of Beloved, the “girl who waited to be loved and cry shame” (Beloved) before she broke into pieces, suggest that the subjective agencies of those who died under slavery persist.

Forms of Disembodied Consciousness

The disembodied consciousnesses of black people are also portrayed in her fiction, as I describe it in the blogpiece A Ghost with a Sword What some might term “ghosts” (Beloved) or even “doors or windows” into other worlds (Paradise): these presences form another lynchpin in Toni Morrison’s anti-racism. Past, present, and future boundaries are porous, and death is not the end. This is a deeply spiritual layering in Morrison’s Beloved trilogy, with suggestions of ancestral regeneration as a figure in one novel—the girl Beloved—seems repeated in the next—the berry-black woman named “Wild” in Jazz. Paradise punctuates the trilogy with the “coal-black” woman on the otherworldly beach on the last page.

Three large groupings of blogpieces here—the Geography series, the Emotions series, and the Musicality series—are fundamentally about African American histories, African American emotional intelligences, and African American artistic expressions. Each of my blogpieces is in some way an attempt to inspire fruitful discussion among Morrison’s readers about a more anti-racist society.

Runner Lorena Ramirez by Christian Palma /REI Co-op Journal

As musicologist Ingrid Monson puts it in her work Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa:

Indeed, aesthetic practice in twentieth-century America—musical practice in particular—has been extremely important in imagining a freer society than the one we inherited. (Monson)

American Writers, Race, and Justice

I will always see Morrison’s Beloved, Jazz, and Paradise trilogy as solidly belonging to the most central, though not always visible, vein of American literature: the deep and sustained questioning of freedom and equality, this jugular vein of the nation’s founding principles. I believe along with literary critic Eric Sundquist, who writes in To Wake the Nations, that

“slavery—especially as it is understood as the governing aspect of a revolutionary ideology articulated by both whites and blacks, often, but not always, in radically different ways—is the overarching American issue, and . . . it remains so, as memory and as unresolved social crisis, into the modern period.”

“Given the long failure of American legislation, jurisprudence, social theory, and artistic endeavor truly to erase color from our consciousness ,” Sundquist continues, it is difficult not to believe that race “remains very much at the center of the American experience.”

To write about the work of Toni Morrison, one must engage the questions of justice and value for all. Patricia Williams, Columbia Law School professor emerita and author of The Alchemy of Race and Rights among other works, has this to say about such justice:

Justice is a continual balancing of competing visions, plural viewpoints, shifting histories, interests, and allegiances. To acknowledge that level of complexity is to require, to seek, and to value a multiplicity of knowledge-systems, in pursuit of a more complete sense of the world in which we all live.’” (Williams quoted in Sundqvist)

Thought Catalog from Pexels

Seeking and valuing a “multiplicity of knowledge systems” is an apt description of Toni Morrison’s accomplishments in language, both in fiction and non-fiction. However, also among Morrison’s accomplishments is her works’ de-coupling from a powerful knowledge-system: namely, what is called “late capitalism”; that cover-up term for a political economy growing fat and greedy on the back of American “chattel” slavery beginning in 1619 and morphing on and on to the present day.

Responses Invitation: Reflect, Write, Post:

How do you think about Morrison’s work in terms of “blowing up the race house,” her words for her project in the novel Jazz? How can her work fight racism?

Up next in this series: Autobiographical Reflections on Race and Response-ability.