“Human, All too Human:” Toni Morrison’s James Joyce.

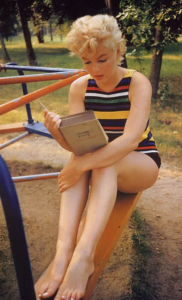

Marilyn Monroe reading Ulysses /Photo by Eve Arnold

Jazz’ narrator is wily and temperamental, which is why she may be “talking back” to another narrator in another novel: Molly Bloom at the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses. The nameless narrator of Jazz exemplifies a type of intertextuality that Morrison has developed between characters in different novels. Toni Morrison’s Beloved Trilogy considers whether or not the figure of Wild in Jazz is a type of “cross over” figure for the girl Beloved and the “coal-black woman” on a beach and cradling another “with tea-colored hair” in Paradise‘s epilogue.

In this blog, I will feature the intertextual connection that Toni Morrison possibly makes with James Joyce. WAIT! Don’t fold yourself up and away from this blog if Joyce sounds intimidating and/or boring to you. Marilyn Monroe read Ulysses in a way you can, as well. More on Marilyn in a minute.

So for the pleasure of thinking about how Morrison, that intermedial jazz musician, “riffs” off of the canonical literature she knew so well:

This blog will offer a rich example of how Morrison “riffs” Joyce:

“Riff” is the term that indicates how one musician picks up the chord progression or a melody sequence of another musician and plays with it, recreates it, and for creating various motives from complimentary to critical.

We will dig deep into some textual passages along with some audio recordings, ending with a fabulous Responses Invitation concerning the lines:

Reading and Listening to Stylized Voices

Even if you haven’t read James Joyce’s “Penelope” section of Ulysses, which concludes his masterpiece novel about 18 hours in Dublin, don’t worry! Did you know that Marylin Monroe read Ulysses? According to Eve Arnold, her photographer, she kept the book in her car and explained that she would read sections of it, fascinated by the language. She didn’t read it from beginning to end, which is a daunting task for even grad students in literature (ah, me, for instance). So: yOU tOo cAN READ uLysSes . . .

James Joyce

Before going on to discuss the relevant content in Jazz and Ulysses, I’m providing you with some fun links if you want to take the time to view them. One is Time magazine’s fun article on Marilyn Monroe and Ulysses:

https://time.com/3809940/marilyn-monroe-james-joyce-photo/

And this next fun link is to the marvelous reading by Fionnula Flanagan of the end of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy (the end of Ulysses) about 6 minutes long (or less, just to get a sense of the voice):

http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/brainiac/2011/06/its_bloomsday_l.html

Readers, be thinking about how the written word can to some extent capture the stylized intonation of a character. But if you’re interested in further aural comparisons, you can find a link to Toni Morrison’s audio reading of Jazz here with a free sample play (audiobooks.com).

Let’s go next to Morrison’s study of modernist writers, especially William Faulkner and Virginia Woof, to get a taste of how Morrison might be throwing out intertextual threads towards some stream-of-consciousness (in part) novels.

Morrison’s Intertextuality with Modernist Fiction (early 20th century)

Morrison’s Intertextuality with Modernist Fiction (early 20th century)

Morrison’s Master’s thesis at Cornell University on William Faulkner and Virginia Wolf may have contributed to her “talking back” to modernist fiction, just as her classics minor and her acting with the Howard Players at Howard University may have influenced her talking back to classical Greek drama.

Although Morrison has famously stated that she did not enjoy being described as a writer who is “like” Joyce (“It has nothing to do with my liking Joyce. I d0.” — ClaudiaTate interview), she does say that there is a difference between being cast as another writer’s disciple by critics who cannot or will not go into her work on its own terms (bad) and having her work compared to his, something to which she has no objection (Nellie McKay interview). I think the same attitude applies to her knowledge of so much literature, and why she might have a particular affinity with Modernism. Like Faulkner and Woolf and Joyce, Morrison explores the anti-romantic, ironic side of the human experience with great passion and experiments boldly with language and story structure in order to puncture through the conventional skin of language that has become dull, stultified, and even pernicious. And very diverse experimenting with recursive, rather than linear, story structures.

But let’s get to the feast here: Ulysses‘s Molly Bloom and Jazz’s nameless narrator.

How does the voice of Jazz’ narrator resonate with Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in the “Penelope” episode of Ulysses? The most striking example is the resonance between the last words of each novel. I suggest that what is explicit at the end of Morrison’s work can be read implicitly in the concluding section of Joyce’s:

a fictional persona acting out the instability between authorizing a narrative and deconstructing that authorization.

Or, to clear away the cumulus clouds of narratology, a character/narrator dramatizing her authority over her story while exhibiting signs of instability about that authority! (Mind boggling, yes, but it’s going to be okay.)

Zoltan Tasi /Unsplash

Jazz’ narrator emphasizes the riskiness of this modernist venture by bracketing her address directly to the reader (“you” in her words) as a “secret” she “longed” to share. Telling it, then, is a charged act, making public something which has always been private: the intimacy between the reader and the book: “That I have loved only you, surrendered my whole self reckless to you and nobody else.”

Morrison’s italics in this passage emphasize a fugitive energy, the rogue behavior of a narrator who follows the above confession with “But I can’t say that aloud.” Acknowledging the reader’s hand on her/him–i.e., reaching out to the reader– makes explicit the physical, sensual experience of reading a book.

Perhaps Morrison is directly alluding to Molly Bloom’s voice at the end of Jazz as the narrator becomes aroused by the characters she has wrought, just as Molly arouses herself with her thoughts about romance and sex. At any rate, by reading Molly’s last words–

“yes I said yes I will Yes” (Joyce, Ulysses) from the vantage point of Jazz’ narrator to “make me, remake me. You are free to do it and I am free to let you . . .” (229), readers may bring new meanings and layers of significance to Joyce’s text.

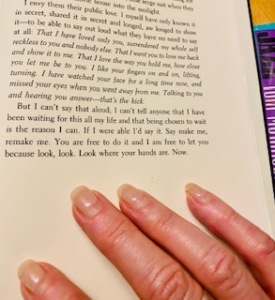

The last paragraphs of Jazz /personal collection

Both endings evoke us, the readers. We actually have some authority in making the meaning of the text. The narrator of Jazz directly addresses her reader (or if you prefer highly technical language, a narratee1) while the secretive and seductive language of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy is more indirect: its implied reader is also a “voyeur,” though, and thus both texts make the actual readers self-conscious in relation to the narrators.

Readers meet the narrators in their co-created imaginaries, then. Morrison actually dramatizes such an arrangement within Jazz with Joe and Violet Trace and Golden Gray and Wild. Briefly (this is difficult to explain): Joe has met the rich, spoiled G.G., and Violet has heard stories about him, but neither knew the other knew this Faulkneresque figure (Golden Gray can be compared with Charle Bon, the mulatto son of Thomas Sutpen in Absalom, Absalom!). Joe believes Wild is his mother, while Violet moons over the stories of Golden Gray. These imaginary or “substitute” loves are parallel to what readers are enticed to imagine with their hands on these books.

Responses Invitations: reflect, write, post:

Please help further the discussion of Morrison’s double-voiced/”indicator and mask” discourse style” by commenting on the ending of Jazz:

But I can’t say that aloud. I can’t tell anyone that I have been waiting for this all my life and that being chosen is the reason I can. If I were able to say it. Say make me, remake me. You are free to do it and I am free to let you because look, look. Look where you hands are. Now.

Ready to go on and on? I suggest the 9th blog cluster, Race and Response-Ability. There are two blogs there so far: “Out here in the real”: Race and Response-ability and Autobiographical Reflections on Race and Response-ability

1 The narratee is the person to whom the narrator recounts his or her narrative; the narratee is frequently a character with whom the narrator interacts. In this sense, the narrator’s “look where your hand is now” in Jazz is addressed to a narratee (Gerald Prince, “Narrative Analysis and Narratology.” The International Society for the Study of Narrative, Item #50). Implied Reader denotes a hypothetical reader of a text. The implied reader “embodies all those predispositions necessary for a literary work to exercise its effect — predispositions laid down, not by an empirical outside reality, but by the text itself.” The next chapter develops in greater detail several central concepts from narrative theory in relation to the experience of reading the Morrison project. (Wolfgang Iser, “Readers and the Concept of the Implied Reader.” The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response.